I’m always interested in learning how others think and frame what they do. Increasingly I feel that the internal dialogue and frameworks we cultivate have a disproportionate effect on how we conduct ourselves in work and life.

Hasard Lee is a US Air Force fighter pilot who has flown over 80 combat missions in Afghanistan, flying the F-16 and F-35 fighter jets across his career.

His book, The Art of Clear Thinking, held a number of useful ideas in their relationship to emergency medicine. This is a speciality that demands clear thinking in order to make (often time-sensitive) decisions, with limited information. This isn’t the same as screaming around the air at 30’000 feet in 1 billion dollars worth of stealth gear while pursued by an F-16, but there is significant overlap between these two worlds in the need to develop the right kind of thinking when working under pressure.

Rather than go through an extensive book review, I’ve lifted some of the concepts and ideas from the book that personally spoke to me.

The ACE Helix

My ability to summon long acronyms to mind is deeply compromised when working under stress. As a simple man, the ACE Helix really appeals. It encapsulates the meta-process of working under pressure by outlining the key steps involved in any mission or work; assess, choose, and execute; simple enough even for me.

A shift in emergency care usually progresses into a ballroom of spinning plates and emerging plans, with agendas and resource limitations layered on-top. Recently, I’ve found applying the following question to any particular case invaluable in gaining clarity:

‘What bottleneck am I in right now?’

This forces me to identify whether I’m in an assess, choose, or execute phase, and where to place my focus.

If I’ve got a decent idea of what is going on with the patient, but remain a bit unsure about what to do next, then I need to push through the ‘choose’ aspect and really narrow down viable options. Maybe its that, on balance, you already feel a chest drain is required, in which case the next step is to optimize executing, and free up bandwidth by focusing on getting the kit ready.

Each time I ask myself to identify the current bottleneck or where I am in a certain process, it normally becomes apparent quite quickly and enables me to push through the next phase with a bit more deliberate focus. Otherwise I’m more at risk of wandering the swamp of half-made decisions, thinking about this possible diagnosis, whilst waiting for that investigation to weigh up the options of what to do next…etc.

Asking the question, “do I need to assess, choose, or execute?” acts as a forcing function to push forwards.

Power Laws

I’d never explicitly thought about this, but a crucial skill in any field is the ability to recognise and work with power laws. These are phenomena that are not subject to linearity, but rather have significant 2nd, 3rd and so on order effects downstream.

Lee talks about the importance of recognizing laws of exponential growth (pathogen infection springs to mind), diminishing returns (over-investigation and poor healthcare resource utilisation may be an example), long tails (80-20 phenomena) and tipping points (in my world this could be transfusion thresholds, 8 kPa on the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve, mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg, a pH of <7.2, etc).

In other words, it’s worth remembering that there are many areas within medicine (or any field) that follow non-linearity laws. By keeping our eyes open, we can leverage actions that exert a disproportionate influence on patient care, avoid blind-alleys that yield diminishing returns and waste resources, and recognise trends and act before a tipping point is reached.

Not every action and decision is weighted equally, and the more expert are able to leverage actions to forge ahead, rather than get bogged down.

Uncertainty

Whilst striving to apply our own order to the chaos around us, its also helpful to recognise that uncertainty is inescapable.

‘Although humans crave certainty, all decisions come with uncertainty and risk’.

Hasard lee

This is an inescapable, existential truth, and I’m somewhat more at ease when I remind myself of it. Nothing in medicine is perfect or certain.

All risk scores, blood tests, scans and investigations have a false negative rate; that is, they miss things. A low risk HEART score for chest pain, which is often used to discharge patients, has a false negative rate of 1-2%. This is despite a survey showing more than half of emergency physicians being uncomfortable with a miss rate of 0.1%. There can be a large gap between what risk we feel is acceptable, and the risk we must accept as dictated by reality. Unless we want to angiogram every chest pain.

“The real world is complex, and decisions always come with some amount of uncertainty…however, by thinking critically and embracing uncertainty, we can come up with better decisions. This isn’t to say that every decision will be perfect, but at a minimum we can eliminate the bad options, giving us a much higher probability of success over time”.

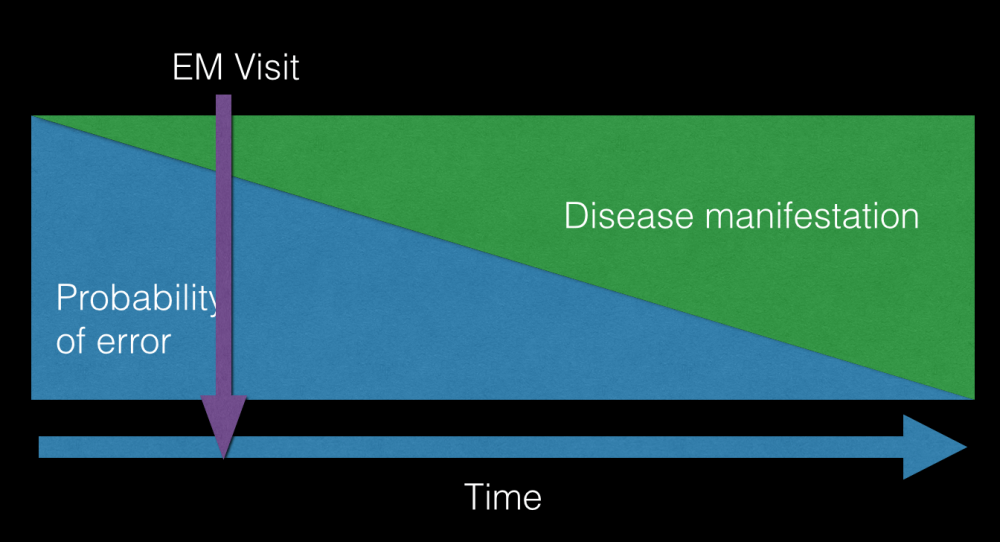

For Lee, regarding decisions that can be altered and adjusted over time, its often best to decide early and adapt as more data emerges. This is the idea behind giving antibiotics as early as possible when somebody triggers alarms for sepsis. We treat what’s in front of us as best as we can, even if later on it emerges that the patient just had a more benign viral illness or something totally unrelated. Uncertainty is at its highest in the beginning of the patient presentation.

Fast-forecasting

This is a technique that Lee adopts when forced to make a decision with limited time or information. There isn’t much fancy to the idea; it’s essentially the act of rapidly forecasting ahead what the likely outcomes of any given decision may be, in order to narrow down to the ‘best’ one. In a less acute example, this may be deliberating whether to discharge the frail patient home at 3am, or whether to empirically thrombolyse the hypotensive patient with a possible PE based on a bedside Echo.

“When we’re forced, on the spot, to estimate the expected value of a decision, there’s nowhere to hide. We can’t push of the decision to someone else or a computer. We must use the concepts, principles, heuristics, and information that we’ve learned over our lifetime to arrive at a solution…no matter how difficult a decision is, you can, on your own, come up with the expected value of it.

It’s a starting point that holds you accountable for understanding the relationships within a system…fast-forecasting a solution prevents us from giving up our most valuable resource; the ability to think critically.”

Hasard Lee

This is really what medical school, countless exams, personal development, courses, regional teaching, podcast listening, clinical-curiosity driven self learning is all about. There are debates online right now about what use a doctor is when there are guidelines for seemingly everything.

It’s this ability to synthesise all the learning, concepts, heuristics, experiences, and hours, and distill it down, in the moment, to a clear decision that can cut through murky uncertainty.

The urgency effect

This is the phenomenon of a seemingly urgent task commandeering our attentional resources and energy at the expense of other objectives.

Emergency medicine is absolutely chock-full of the urgency effect: checking ECGs, a quick paracetamol prescription for that person in the waiting room, reading a blood gas put under our nose, picking up the phone to the relative asking for an update, and so on and so on. Lots has been said by others about the huge effects on attention residue, efficiency, cognitive overload etc of these task interruptions.

A task may be urgent, but unimportant. Although the urgency effect will naturally galvanise our attention toward the issue, its important to recognise when addressing an urgent but unimportant (or less important) task, and triage accordingly. Urgent, unimportant tasks cannot be attended at the expense of urgent important tasks. This sounds obvious, but the distinction is sometimes opaque and less clear in reality.

Lee asserts that you must always leave enough bandwidth to see the big picture and prioritise the list of never-ending tasks. Once you get 100% task saturated, you’re no longer in control.

Effects over tools

Sometimes we can be so process oriented that the means of achieving an outcome takes precedence over the outcome itself.

Effects-based operations (EBO) is a strategic approach that emerged during the Persian Gulf War, to combine military and non-military methods in order to achieve a specific outcome. The tool or process is not as important as the effects it generates. Rather than being wedded to a particular way of meeting an end goal, rather start with the desired outcome and find solutions that can encompass uncertainty and remain flexible.

When applied to emergency medicine, I’ve found this way of thinking useful in delineating “what outcomes do I need for this patient”.

This is encapsulated in a good ‘impression’ and ‘plan’ in the documentation, but starting with the things that need to be achieved, then working toward them in a flexible way, reduces the risk of getting stuck waiting for the right tools. Deciding on the headline outcomes needed for each patient, early in the interaction, orients me better.

A recent example with a complex presentation was boiled down to:

- Ascertain whether CT imaging is needed

- Engage psychiatric liaison team

- Address safeguarding needs

We ran into some roadblocks along the way, but being clear about these 3 end outcomes, early on, enabled us to be flexible and find ways to achieve them.

Take ownership

Debriefing in medicine can sometimes be cursory, if it even happens at all. A ‘hot’ debrief is often helpful to just emotionally process a significant event as a team or individual. But a ‘cold’ debrief can be performed as an individual or team in order to iterate improvement.

Lee recognises the proclivity of people to want to be seen in a positive light. This makes the debrief a potentially threatening concept. To do it right, there have to be fundamental conditions built in.

‘The pilot with the most experience must be willing to say they made a basic error…By treating everyone equally in the debrief, the mission can be analysed in a sterile environment’.

Everyone must be treated equally in a debrief. This helps de-personalise the process, and shift the focus toward extracting lessons for the benefit of everyone. When we feel like we have a certain image or status to maintain, we may be less willing to take a more objective look at the situation, and so miss out on vital learning.

If these preconditions are met, although it may appear a brutal process to an observer, the pilots (or clinical staff) in the debrief are really just engaged in a collective puzzle on how to get better.

The process that Lee outlines is as follows:

- Reconstruct the event: amalgamate everyone’s data into a god’s-eye view of the event. Elicit high level info in a precise format from each person to reconstruct a high resolution map of the event that is shared by everyone.

- Analysis phase: prioritisation is key in choosing the high yield ‘focus points’ that can be learnt from. Applying the ACE helix to each focus point (where things could be improved) delineates whether it was an isssue with analysis, choice, or execution that lead to what happened.

- Instruction phase: where everything that was learned comes together and is reflected back, tying the lessons into larger concepts and how they can be applied to real-world practice.

The ideal outcome is to never make the same mistakes twice, or as Dan Dworkis says, ‘commit to never waste suffering’.

I’d recommend his book, The Art of Clear Thinking. His YouTube channel is also pretty great for seeing some real life Top Gun in action.